|

[2] The north end of the wall and the tower from the south

west. The outer ditch was on the line of the carriageway.

[3] Detail of loop on the outside or west face of the wall.

[4] Detail of a splayed loop on the inner or east side of the wall

south of the tower.

[5] The inner side of the tower from Chapelfield Gardens drawn

in April 1853. [Norwich Castle Museum and Art Gallery Vol D141 DC page 3]

[6] The tower and the north end of the wall from the north west.

[7] Buttress on the external or west face of the wall immediately north of the tower.

[8] Brick refacing on the inner or east face of the wall south of the tower.

[9] Blocked doorway in the wall south of the tower from the outer or west side.

[10] Archway through the wall south of the tower from the outer or west side.

[11] Archway through the wall from the outer or west side.

[12] Archway through the wall from the outer or west side.

[13] Doorway cut through the wall with brick arched head at the south end of the wall. From the west or outer side.

[14] External face of arch.

[15] The south end of the wall from the north west. The outer ditch was on the line of the modern carriageway.

[16] A window opening (?) and brick repair on the outer or west face of the wall at the south end.

[17] Detail of putlog showing that on this section of the wall the side bricks were laid horizontally.

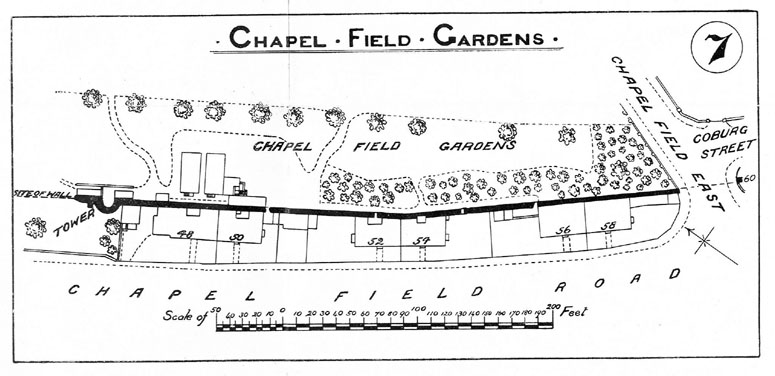

[18] Plan of the section of wall on the west side of Chapelfield Gardens published in the report of 1910.

[19] Water colour of a doorway by H Ninham said to be in the Chapelfield section of the wall.

[Norwich Castle Museum and Art Gallery 1894 76.1054: F]

[20] The outer face of the tower from the north west published in the report of 1910.

[21] Photograph of the wall from the south east, from Chapelfield

Gardens, published in the report of 1910.

|

Historical Background Report

General description of the historic fabric

The surviving wall is on the west boundary of Chapel Field Gardens

and runs from the remains of a tower at the centre of the west side

to the south-west corner of the park.

[22-01 Map] The standing section is 137 metres long and is on relatively

level ground on a line running from the north west to the south east.

The wall bows outwards slightly towards the centre towards the line of

the ditch that was on the south-west side of the wall.

[22-02 Plan] The surviving part is approximately 4 metres high but

it has lost all of its outer parapet that would have added almost 2

metres to the height and in many parts much of the upper part of the

wall has also been lost.

[2]The position of surviving loops suggests that the present level of

the ground inside the wall is close to its medieval level.

The wall is now on average 1.2 metres thick but at several points

is as much as 1.8 metres thick. Map evidence suggests that there have

never been substantial buildings against the inner side of the wall and

in many places the inner face of the wall is essentially intact though

repaired and re-pointed.

[22-04 Int Elev]This is exceptionally important here ... elsewhere,

on other sections of the wall, the inner wall face was badly damaged

and much evidence lost when 18th and 19th-century buildings against

the walls were demolished. At Chapel Field there are no actual remains

of an internal arcade to support a wall walk and there is no evidence

on the internal face of the wall, in the form of brick ends or the

shadow of arches, to suggest that an arcade has been removed. The

conclusion at this stage must be that there was not an arcade here

but the explanation for this difference has to be conjectural. Either

the wall was one of the first sections to be built, before the form of

the arcade supporting a wall walk had evolved, or, less likely, the

position of the wall meant that strategically the wall here did not

merit an arcade and wider wall walk.

On the outer side of the wall are the remains now of five brick

lined loops [22-03 Ext Elev] but on the inner side, where the wall

face is less disturbed, there are eight regularly spaced loops. A

ninth loop can be inferred, from the regular spacing of the loops,

to have been lost where a gateway was cut through in the 19th century.

The apex of the arch of the loop embrasure is not level but slopes down

slightly from the apex of the arch on the inner wall face to the top

of the loop on the inner line of the embrasure. [3 & 4]

These loops are just over 6 metres apart. This, in itself is also

significant, for where the arcade was an integral part of the construction

of the wall, the loops, central to each arch, are only about 4 metres

apart.

One specific problem for an interpretation of the evidence here,

is the lack of evidence for the width and the form of the wall walk.

If the wall was as much as 1.8 metres wide then it had much the same

overall thickness as those sections that were built with an inner

arcade. At the Black Tower the outer parapet is only about 450mm wide.

There is also an inner parapet at the steps up to the tower but further

along the wall the inner edge of the wall walk has broken away and

evidence for the existence of an inner parapet has been lost. Would

an inner parapet have been needed on the main sections of the wall?

It depends in part on how the wall walk was meant to function. Was it

an intermediate platform where fighting troops, specifically archers,

could take up positions to defend the city or was it primarily a route

between towers for guards patrolling? If the wall at Chapel Field had

an inner and an outer parapet of about 500mm then the space left for

the wall walk would have been about 800mm (or 2'6") wide providing

little space to manoeuvre. The only section of wall where an inner

lip of flint implies that there was an inner parapet is at Magdalen

Street and much of that evidence is close to the site of the gate where

any inner parapet may have been constructed to protect the steps up

into the gate.

The tower at the north end of this section was the third intermediate

tower south of the gate at St Giles.[5] It is semicircular in plan,

5.3 metres across and projects into the ditch by about 2 metres.

[22-05 North Sec] This is one of the smaller towers ... intermediate

towers elsewhere are generally between 6 and 7 metres in diameter.

The tower has lost much of its upper part but still stands to a height

of 6 metres rising higher than the flanking walls. The outer face has

one area of patching on the south side that might cover the position

of a loop. On the upper level there is evidence for two loops on

the outside where brick work survives on the south and south west

sides and on the north side on the inner face there is a large area

of blocking in brick which may indicate a third loop.

On the inner side of the tower at the ground level all the medieval

fabric and any evidence of the plan and form of the tower is covered

by the modern toilet block set within the tower. If the tower was like

other towers on the circuit then there would have been loops set to

provide sight lines from inside the tower out along the outer faces

of the flanking walls.

What evidence there is at the upper level would suggest that the

tower was open on the inner side. The survival in part of a rough

inset in the wall of the tower just above the roof of the toilet is

probably where the wall walk continued round into the tower. If, and

less likely, the tower was closed on the inner side, then the off set

could have supported the timbers of a roof or platform at that level.

The wall continues for just over 4 metres north of the tower before

now tapering out. There is a raking buttress in this section on the

outer face of the wall with brick corners which is presumably part of

a 19th-century repair.

[6 & 7] The flanking walls of the tower do not simply butt up to

each side. On both the north side and the south side the wall is

angled outwards slightly a metre or so before the tower. It is difficult

to see now if this is a significant medieval feature, that might

suggest the tower pre dated or post dated the wall or it may simply

reflect awkward repairs or re-facing.

On the inner side of the wall, behind the nursery school, part of

the bank against the wall survives.

[8] To the south of the gateway at the boundary between the school

and the depot, the bank has been in part removed and has exposed the

looser flint and mortar walling of the footings.

The wall to the south of the tower has 5 narrow gateways cut

through it. [9, 10, 11, 12, 13 & 14] These date from the 19th

century and were constructed to provide private access into the Gardens

from the yards of the houses built against the outer face of the wall

when the ditch was filled in.

At the south end of the wall there are more extensive areas of

repair and rebuilding with sections of brickwork.

[15 & 16] There is one loop surviving on the inner face just

over 4 metres from the south end. The evidence for the spacing of

the loops here is less certain but again there is a general pattern

of loops every 6 metres. One area of brick under building looks a

little as if this covered a drain running out to the ditch.

Along the outer face of the wall is a single level of putlogs

suggesting that the wall here was raised in two lifts to the level

of the wall walk. Elsewhere there are two levels of putlog holes

implying three lifts. The putlog holes at Chapel Field are not logically

spaced and do not relate specifically to the spacing of the loops

although the putlogs are set at about the level of the top of the

loops which meant that scaffolding timbers could have been set up

through the loop. The bricks on the sides of the putlog holes are

set flat and laid running out from the putlog with two courses and

with single bricks laid across the top, laid parallel to the line

of the wall. [17] Elsewhere the side bricks of the putlogs are

generally laid with vertically set bricks.

Documentary evidence

In a Leet Roll from the 16th year of the reign of Edward I

(1255/1256) the millers of the Prior of Buckenham had undermined the

ditch between St Giles Gate and St Stephen's Gate and 'made a purpressure

under the walls.' The Prior's mill was in 'Chapply Field'

and purpressure generally refers to illegal enclosure or fencing in of land.

[Fitch page 12] The document specifically refers to walls ... in other

13th century documents other sections of the defences are described

as the ditch.

Furthermore, in 1266 or 1267 John the Carpenter sold all 'his

said messuage lying near the Gate of Needham', (St Stephen's

Gate) to the Citizens and Commonality of Norwich, 'for their more

convenient building of the wall of the city there.' [Dom.Civ.

quoted by Fitch page 12]

Blomefield cites the last leaf of the Book of Customs, which notes

that along this stretch of wall between St. Giles and St. Stephen's

gates were 229 battlements on the walls and towers.[Blomefield, page 98]

Chapel Field takes its name from the chapel of St. Mary which

used to stand in the grounds. Blomefield notes that in 1402 this

chapel was a meeting place for assemblies. [Blomefield, page 119]

In 1406 the citizens of Norwich 'claimed four acres and an half of

ground which belonged to Chapel in the Field ... lying in Chapel-field

Croft, within the city ditch, on which it abutted south ...'

[Blomefield, page 124]

In 1549, at the time of Kett's Rebellion, soldiers made several

breaches in the walls, betweeen St Stephen's and St Giless

Gates 'which were broken open at my Lord of Warwicks comyng.'

[Comp. Camerar cited by Blomefield, page 248]

In the 17th century Sir John Hobart of Blickling seems to have used

Chapelfield House as a town residence. This was on a large plot of

land now within the Nestle factory site. He took a 40 year lease on

the open land later to become Chapel Field Gardens with...

' the right to take musters and mustering of men and horses

and exercising them in military discipline and also for pitching

of any tents for the use of musters and for the erecting and making

of Butts ... and also for repairing the city walls and to pitch stages

for that purpose.' [Cozens-Hardy, page 372]

The Norfolk Annals for 1852, compiled from articles

in the Norfolk Chronicle, reports, on the 17th of April,

the opening of the pleasure gardens by the Corporation [Annals, vol. I,

page 11], while an entry for 1867 explains that after being closed

for some months, the gardens were re-opened, with 'several portions

of the city wall ... removed, and railings erected, and efforts ... made to

level the area.' [Annals, vol. II, page169]

Map evidence:

Cunningham's map of 1558 is actually a view of the city from

the west. The Gate of St Giles is almost central to the view and

Cunningham shows clearly the triangle of open ground that is now

Chapel Field Gardens. The space has cattle grazing and human figures

that appear to be archers practising. There are only five towers

shown between the gates for Cunningham omits the sixth tower

immediately before St Stephen's Gate.

In the late 17th century and throughout the 18th century all the

cartographers have problems deciding which of the six towers were still

standing. Kirkpatrick, generally very accurate, shows only five towers

about 1714 but appears to have omitted the tower at the south end of

this section at the end of the street that is now called Chapel Field

East. Cleer in 1696 shows four towers ... the now lost tower north of

this section, the surviving tower in this section, the lost tower at

the end of Chapel Field East at the end of this section and the polygonal

tower on Coburg Street. He omits both the first tower after St Giles,

the Drill Hall tower that actually stood until 1970, and the sixth

tower by St Stephen's that is still standing. Hoyle in 1728 and

Blomefield in 1746 missed out the same towers. Hogenberg and Braun in

their version of King's map of 1766 show all six towers standing

and all are shown in approximately the right position although the

surviving tower in this section is shown slightly too far to the south,

too close to the corner of the gardens.

Perhaps the single most important thing shown by the maps is that

this section of the wall has always been clear of buildings on the city

side. Elsewhere in the city, damage and deterioration of the face of

the flint work has been caused primarily by the demolition of houses

that had been built against the walls in the 18th or 19th century.

Here there is little reason to doubt that the wall face on the inner

side is, ostensibly, the medieval wall face be it repaired and re-pointed.

This is particularly important here. The lack of evidence for an

arcade supporting a wider wall walk would imply that there has never

been an arcade along this section despite evidence that the external

appearance of the wall, with widely spaced loops paired with embrasures

in the battlement, would have been the same as elsewhere.

Hochstetter's map of 1789 shows the wall from St Giles Gate to St

Stephen's standing without breaches though he does not indicate

the fourth tower at the south-west corner of the park at the south

end of this surviving section which implies that it had gone by then.

By 1830, the date of the map by Millard and Manning, the wall at

the end of Chapel Field East had been breached and the road continued

through to join the road outside the ditch, by then called Chapel Field

Road. There were also three pairs of houses widely spaced and built

against the outside of the wall on this section. These are shown in

more detail on the first edition of the Ordnance Survey map in 1884.

[sheet LXIII.15.2] Four of these houses had gateways cut through the

medieval wall to provide private access into Chapel Field Gardens.

These gateways remain today as narrow breaks in the wall.

A sketch plan of this section, published in the report of 1910,

shows clearly the arrangement of the houses built against the outer

face of the wall, over the line of the infilled ditch. [18]

Historic views and historic photographs:

Henry Ninham's undated 19th-century water colour, 'Part of

the Wall by Chapel Field Gardens' (NCM 1054.76.94) shows a doorway in

the wall, with a wooden door in situ, with brick edging to

the top of the arch. The inner mouldings are of stone. The wall is

visible to the right and left of the door, but not to the height of

the battlements. What appears to be a putlog hole is visible to the

right of the door. [19] The precise location of the doorway is unclear.

The two photographs of the wall and the tower published in the

report of 1910 [Collins' 1910 plates 18 and 19] are particularly

unhelpful as the defences are completely obscured by ivy and other

undergrowth. The view of the tower from the north west does show

the raking buttress on the outer side which shows that it is not

20th-century work. [20 & 21]

Archaeological reports:

A number of small-scale archaeological excavations have been

undertaken in this area. Generally most records are part of a

watching brief or notes made as trenches were dug for services.

- The construction of a new roundabout at the north end of

Chapelfield Road (TG22460848) overlays part of the city wall,

which is marked out by a band of flints. [SMR NF206, 1969] This

is the section of lost wall at the north end of Chapel Field Gardens.

- An excavation at 42 Chapelfield Road in 1972 by J. Roberts for

the Norwich Survey examined the nature of the city wall foundations.

Trenches dug at right angles to the city walls found that the

foundations were very shallow, and had been cut into the natural

sand. The fillings of the city ditch along this stretch of wall

were found to be late 18th- and 19th-century rubble. [SMR NF236]

- An excavation for a sewer by the City Engineers, along 44-58

Chapelfield Road, prior to construction of the ring-road in 1973 took

place within the fill of the city ditch, and revealed that the fill

was mainly of foundations and modern demolition/backfilling. [SMR NF196]

- Sewerage trenching operations were undertaken outside the city

wall in 1974, in advance of the inner link dual carriage way (60-102

Chapelfield Road). These trenches extended north-east to south-west

along the outer side of the city walls and revealed 'Disturbance

almost wholly of 18th century - 20th century from houses backing

onto city wall and rubble from their demolition. ' [SMR NF196]

- In 1975 the construction of the underpass for the inner link

road was dug from inside the city wall to the west pavement of

Chapelfield Road. [SMR NF260] No trace was seen in this section of

the defence ditch.

- SMR NF372 gives quite a full account of the transition

of the area, and a secondary file exists, but does not contain much

information of use which is directly relevant to the walls or towers

in this area.

- SMR NF260 reports the finding in 1972 of an iron staple

from the flint and mortar buttress of the city wall opposite Caley's

main gates. The buttress was partly demolished by an articulated

lorry pulling into Caley's. The iron staple is apparently part of a

door fitting. Caley's was later the Nestle factory.

- Department of the Environment Report HSD9/2/1005 pt 6 (contained

in Gressen Hall file 384) mentions maintenance work to be carried

out on the section of wall and towers from Chapelfield Road North

to St. Stephen's Gate in 1988.

- In July 1997 trial trenches were dug at the south end of this

section at the north entrance to the Nestle site. [Drawings SMR File 384]

CONDITION SURVEY

List of known repairs:

Not available at this stage. Presumably work previously undertaken includes:

- the alterations to the tower to create a public urinal for

the park about 1870

- construction of the buttress at the north end of the wall

in the late 19th century

- extensive making good and re-facing of the outer side of

the wall after the houses in Chapelfield Road were demolished

before 1973.

Principal conservation problems:

The condition of this whole section is generally quite good and

no urgent repairs or consolidation works are required. However

there are a large number of small areas of lost flints or inappropriate

cement based pointing that should be attended to. Perhaps one short

concerted programme of work should be planned to resolve all these

small problems in one go.

1. Fractures implying settlement

Despite the proximity of the road and its heavy traffic on the

outer side, there is little evidence for settlement or stress caused

by vibration. However, this should be monitored and the situation

reassessed yearly or perhaps biannually so remedial work can be put

in hand before problems develop too far. Cracks on the outer face

of the tower look like long-standing faults but again these should

be reassessed annually.

2. Shedding flints on the face and top of the wall

- Areas of loose flints on the face of the tower should be re-pointed.

- The top of the wall in the south half should be re-pointed and

the run off of water improved before there is further deterioration.

- Much of the facing flint at the south end of the low section of

wall on the outer side has been lost. This area should be re-pointed

and loose flints reset.

- At the south end on the side towards the park the area up to

the brick quoins should be re-pointed

- An area of lost flints against the brick towards the top should

be replaced to stop further deterioration.

- The area around the window like opening at the south end should

have cement mortar removed and be re-pointed.

- At loop on inner side by south gateway check bedding of flints where

bricks have been lost.

- At the south west corner of the school area there is a large

area of the wall face with cobbles that are over pointed with a

cementitious mortar that should be raked out and the area rep-pointed

more carefully with a lime based mortar.

- Generally behind the school buildings areas of loose flint should

be repointed and lost flints below the area of brick under building

should be replaced. See notes on drawings.

- On the road side of the wall there are several areas where flint

has been lost. In this patches flint should be replaced to form a

flush face.

3. Intrusion of woody stemmed plants

General problem as elsewhere.

- On inner face immediately north of south gateway remove

vegetation and where necessary re-point cavities where plants

removed.

- On inner side of wall between the two gateways at the south

end there is a large cherry tree that is too close to the wall

and is probably damaging the wall with its root system. This

should be removed.

- The area of wall behind this tree and to its north has some

vegetation that should be removed and cavities in mortar where

roots removed should be re-pointed.

- On inner side immediately south of toilet remove vegetation

along top of set back.

- On the outer side of wall north of tower there is a self-seeded

silver birch and a buddleia that should be removed and areas where

the roots have damaged the mortar should be re-pointed

4. Deterioration of the brickwork

Not generally a problem in this section. The brickwork of the

loops behind the school building are generally in a good state of

repair and are sheltered from the worst of the weather.

|