|

[2] The outer side of the wall from the south east from King Street.

[3] Loop on the exterior or south side of the wall.

[4] Loop on the exterior or south side of the wall.

[5] Loop on the inner or north side of the wall.

[6] Brick head of the loop.

[7] Detail of a putlog.

[8] Blocked doorway on the inner or north side of the wall.

[9] Brick slots on the exterior of the wall below the medieval ground

level.

[10] Looking up to the Black Tower from the river. [Norwich

Castle Museum and Art Gallery FAW 688]

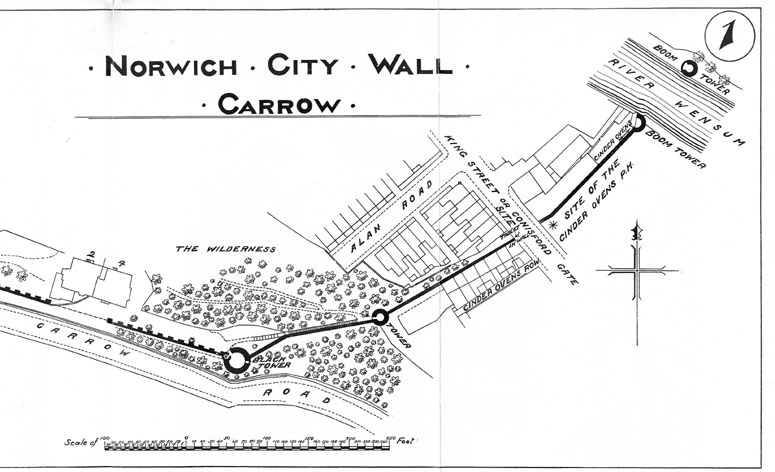

[11] Plan of the wall published in the report of 1910.

[12] Photograph of the exterior of the wall and the lower tower

published in the report of 1910.

[13] The east end of the wall from the south.

|

Historical Background Report

General description of the historic fabric

The surviving part of the wall is 45.3 metres long and roughly 1.6 metres thick.

[34-02 Plan] The line of the base of the wall drops 5 metres in the short distance from the west end to the level of King Street at the east end.

[2]

The profile or scar of the wall against the lower tower [report 33] shows that the wall had a narrow wall walk and a high outer parapet but this has been lost on the surviving section. The scar would suggest that the parapet was only 920mm high where it abutted the tower where it is closer to 2 metres on other sections of the wall. This may simply reflect the way that both the wall walk and parapet was stepped down as it descended the hill. From the tower the wall walk may have dropped several stages while the parapet continued on a level for further before being stepped down. In fact only the first part of the wall may have been steep. The scar of the medieval ground level on the outer side indicates that possibly the ditch dropped more rapidly than the wall top. A report by the Ministry of works in 1953 (see below) implies that at that stage brick work from the battlement on top of the parapet survived but these have since been lost.

There are four loops surviving on the outer face of the wall with surrounds in brick.

[3 & 4] There was almost-certainly a fourth loop where there is now a blocked opening and possibly a fifth loop hidden behind the dense undergrowth at the centre of the wall. Only two of these loops at the west end of the wall can be seen on the inner face of the wall.

[5 & 6] These loops have wide internal splays formed in brick. The area of wall on the inner side of the third loop has been heavily re-pointed suggesting that the wall has been refaced. The lower part of the wall to the east behind the blocked opening and lower down the wall has certainly been refaced with a large proportion of the flints being pebbles.

[34-04 Int

Elev]

There are a number of putlog holes surviving. [7] The three putlogs at the top of the wall on the south side probably mark the height of the wall walk. Elsewhere the parapet appears to have been raised as a separate lift with any scaffold resting directly on the wall walk. It is even possible that the parapet was built overhand from the wall walk without scaffolding.

The south side of the wall has several areas of blocking and repair in brick from the demolished 18th and 19th-century cottages. At the west end is what appears to be a doorway with a brick-arched head though on the north or footpath side it is cut by the ground level and was probably actually a window.

[8] There are several areas of brick blocking where cross walls of the cottages had been stitched into the flint work but then cut back when the cottages were demolished. At the centre of the wall is a curious area of wall underbuilt in brick which is laid to form closely spaced vertical channels.

[9]

Documentary evidence:

In the early 13th century, the land inside the wall was held by a priest, Nicholas de Berstrete. About 1216 he granted the land to Sibrand Prat for 30 shillings. This included part of the land

'which was John le Botelers, from the Gates of Berestrete, lying between the land of Carrowe and the King's way, which extendeth from the Gates of Berestrete to Conesford in breadth, and in length from the Ditch of the City to the Pathway which extends from the King's way aforesaid to the Church yard of St Peter of Southgate.'

[Fitch, page 1]

This was a very large piece of land covering all the steep hillside from Ber Street Gate to King Street and everything south of that. The document shows clearly that the city extended as far south as Conisford Gate by the early 13th century and there was already a ditch marking the city limit which presumably followed the present course of the wall down Carrow Hill. It is also interesting to note that although Boteler owned the property in the 12th century his name survived for Carrow Hill is referred to as Butlers Hill until at least the 19th century and the Black Tower was variously referred to as Botelier's Tower or Butler's Tower. Ann, the daughter of Sibrand granted this property, to the Church of St Mary along with all her tenements in the city and a mill 'before the Gates of

Berstret.'

In 1451 and 1481 the Agistment for the Walls records that South Conesford Ward were responsible for the repairs to this stretch of wall.

[Liber Albus, f. 177; Hudson & Tingey, vol. II, pages 313-5]

Map evidence:

Maps from the 18th century show that all the wall and all the towers from Ber Street Gate to Conisford Gate at King Street survived. By the early 18th century there were buildings against the outer side of the wall on either side of Conisford Gate (shown in the views of the gate by Ninham) but otherwise no buildings outside the city walls to the south. Hochstetter's map of 1789 shows gardens laid out against the south side of the wall between the lower tower and the building against the outer side of the wall at the east end of this section.

Hochstetter's map shows the position of Conisford Gate but that was removed in 1794 and a small part of the wall abutting the gate on the west side was lost as the road was widened. In the early 19th century houses were built south of the city outside the walls and industrial buildings and wharves were built between the river and King Street, between the Boom Towers and Carrow Abbey. The earliest of these buildings are shown on Millard and Manning's map of 1830. However, because the hill rises so steeply from King Street up to the lower tower, none of these new buildings impinged on this section of the walls.

By 1885, when the first edition of the Ordnance Survey map was published for this area

[sheet LXIII.15.14] the land on either side of King's Street was much more densely built up with terraced rows of small houses and with large industrial buildings many connected with malting. These buildings are shown on a painting in the Castle Museum collection

[10] with a view up to King Street from the east bank of the river.

[NWHCM: FAW 688:

unattributed]

There was a terrace of small houses called Cinderovens Row built hard up against the outer or south side of the wall. On the inner or city side of the wall there was a large maltings or malt house facing on to King Street. The map indicates that this was either built over the narrow alley inside the wall or was bridged over the alley and built up and over the medieval wall.

The maps do not show when the wall immediately against the lower tower was breached and when the west end of this section of the wall was lost. Morant's map of 1873 and the sketch map of this section of the walls published in the report of 1910 show the line of the wall as unbroken.

[11]

Historic views and historic photographs:

The view of the outside of Conisford Gate drawn by John Ninham in 1793 [published by Fitch, 1861, plate opposite page 1] shows a house against the outer side of the wall with two gabled dormers. To the left or west of the house the top of the wall may be depicted with battlements.

Harcourt Bosworth's sketch of the gate actually shows no gate, but a tower to the left of the drawing with vegetation along the top that must be the lower tower on Carrow Hill. Buildings are visible to the front of the picture.

[NCM 1922.135. BH46: INT, date uncertain]

Photographs published in the report of 1910 [Collins, 1910, plates 5 and 6] shows just how densely overgrown this section of the wall was but they do seem to show that by then any crenellations on the wall had gone.

[12]

In the NNAS collection at Garsett House, there is a photograph of the cottages built against the outer south side of the wall. There is nothing in the external elevation or in the caption to indicate any specific function that would explain the odd arrangement of brick slots that survives built into the wall.

Archaeological reports:

There are no archaeological reports that refer specifically to this section of the wall.

CONDITION SURVEY

List of known repairs:

Not available at this stage.

Summary of present condition:

Generally the wall is in very good condition.

It is not clear if the wall was consolidated or underpinned when the houses on the south side were demolished and the site cleared and levelled for the construction of the residence. Certainly the bank down to the road, seen on Ninham's view of the King Street gate, has been cut back and the ground taken back level from the road for some 30 metres.

[2 & 13]

In October 1953 the wall was inspected by staff from the Ministry of Works. The recommendations in their report are still pertinent today and the entry for this section is quoted in full:

3. Cinder Ovens Row

Here the City Wall is preserved to its full height, except for the actual coping. Embrasures servicing the wall-walk can be seen, blocked with later brickwork; only in one other part of the wall are embrasures preserved (5 Ber Street). Visible also are the usual arrow-slits at (internal) ground level, now blocked. Lower still there has been a fairly recent underpinning, because the building of Cottages (now demolished) occasioned the cutting back of the 13th Century town-bank on which the wall is built. This bank is clearly seen beside the inner face of the Town Wall, although that face itself is the product of a modern repair.

This portion of the City Wall, on flat land but leading to a steep slope, is part and parcel of the most important section of the whole scheme. Together the pieces of this section show how the men of Norwich in the 14th Century met and overcame their engineering problems. Their solution was much the same as those of the Royal Engineers at Montgomery and Radnor, but the walls of the latter are only visible now as grass-grown mounds. This stretch of the City Wall, all of it, is of supreme importance for the history and development of Norwich. It would be nice to have the ditch in front of it exposed and cleared out, once the remaining cottages have been removed. The present appearance of the outer face of the City Wall is, of course, unpleasant, but this can be remedied at little cost. For the most part the walling is genuine and good-looking; after treatment and with a suitable layout in front, with ditch exposed, it could form a most attractive adornment of an entrance into the city.

There is a considerable amount of lose brickwork and masonry along the top of this stretch of wall which must receive urgent attention due to free public access. In addition, there are several areas on the south face of the wall which are in danger of falling.

Having consolidated the wall-top, removed such modern brickwork as may be necessary and secured the loose areas of face work, it is very desirable to continue the work whilst the scaffolding is in position. In this next phase of the work, the modern brick chimney breast adjoining the cottages should be removed and the wall made good in flint core work, the surface of which must be kept back behind the facing. Similarly, all modern brick patching should be removed and the core work thus exposed, consolidated and left as such except where re-facing is necessary for the safety of overhanging flint work.

All remains of the cottages as now seen on the wall face must be carefully removed and the flint work repointed as necessary in lime mortar. The broken end of the wall adjoining King Street must always be left in rough-racked core work and never 'smoothed over' to suggest a finished end. With care, the arrow-slits may be re-opened and under skilled supervision this wall could soon look very fine indeed.

Urgent: �100. Necessary: �300.

Principal conservation problems:

This section of the wall has few conservation problems apart from the general ones:

- Shedding flints on the face and top of the wall

These should be re-bedded. Small areas of loose flint work on the south side of the wall at the east end should be repaired.

- Intrusion of woody stemmed plants

Vegetation particularly buddleia should be cleared from the walls before they become established

|