|

[2] A photograph of the upper wall from the west published in the report of

1910.

[3] The upper wall from the west.

[4] A photograph of the arcade on the city side of the upper wall from

the east published in the report of 1910.

[5] The inner side of the upper wall from the north west.

[6] The north end of the upper wall from the north.

[7] Upper wall arch on the city side showing clearly the two levels of

putlogs.

[8] Upper wall arch on the city side.

[9] Detail of the brickwork of the arch of the southern archway of the

wall walk.

[10] The loop from inside the third arch from the south.

[11] The north end of the upper wall from Carrow Hill Road.

[12] Detail of a loop on the exterior of the wall.

[13] Detail of putlog on exterior of the wall.

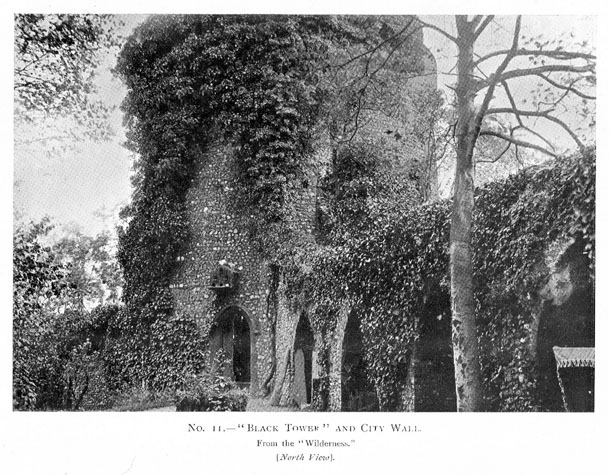

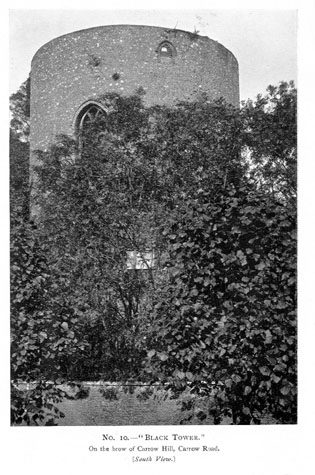

[14] Photograph of the Black Tower from the north west published in the

report of 1910.

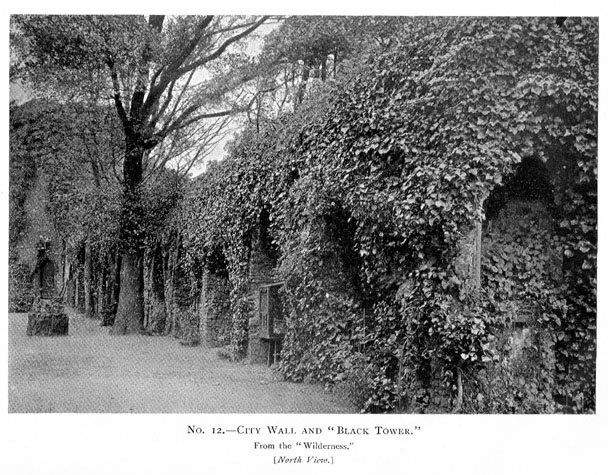

[15] Photograph of the wall arches looking towards the Black

Tower. Published in the report of 1910.

[16] The same view in 2001.

[17] The north end of the middle wall looking towards the Black Tower

and showing clearly the level of the wall walk and the short stub of flint

surviving from the parapet on the outer side of the walk.

[18] The doorway cut through the wall immediately west of the Black

Tower. View from outside the wall.

[19] The doorway cut through the wall immediately west of the Black

Tower. View from inside the wall.

[20] The north or internal face of the middle wall with two levels of

putlog holes between the arches.

[21] The upper part of the tower on the south west side.

[22] The Black Tower from the south.

[23] The Black Tower from the north west.

[24] Looking towards the Black Tower from the wall walk.

[25] The doorway into the tower on the west side.

[26] Doorway into the tower.

[27] Detail of the arched head of the doorway.

[28] Doorway to vice on the west side of the entrance.

[29] The newel of the vice.

[30] The vice from the top.

[31] The brick vault of the vice.

[32] The doorway to the wall walk and the upper part of the stair

turret.

[33] Upper part of the stair turret from within the tower.

[34] Doorway into the vice from the wall walk.

[35] Head of the doorway into the vice from the wall walk.

[36] Ramped parapet wall on the inner side of the steps up from the

wall walk into the Black Tower.

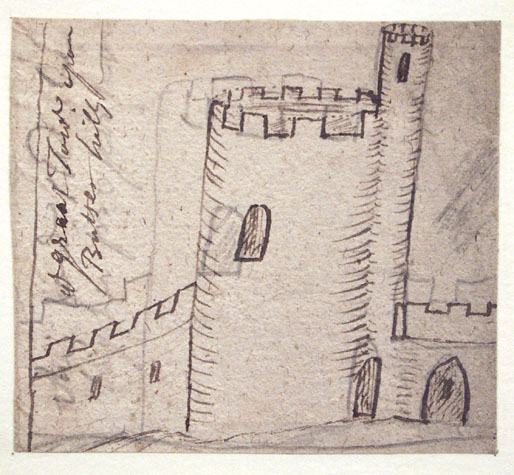

[37] Drawing of the Black Tower from the north in the early 18th

century by John Kirkpatrick. [Norwich Castle Museum and Art Gallery

1894.76. 1695:F]

[38] The doorway into the tower from inside the tower.

[39] Loop and putlog holes on the west side of the tower at the lower

level.

[40] Doorway from the upper chamber into the vice.

[41] The fireplace on the north side of the tower.

[42] Upper part of fireplace with brick work of hood broken back to a

relieving arch.

[43] Loop blocked when the large upper windows were inserted in the

18th century.

[44] Large window opening on the south side of the tower at the upper

level.

[45] The large window opening to the east of the fireplace in the u

pper

chamber of the tower.

[46] The upper part of the tower on the south side.

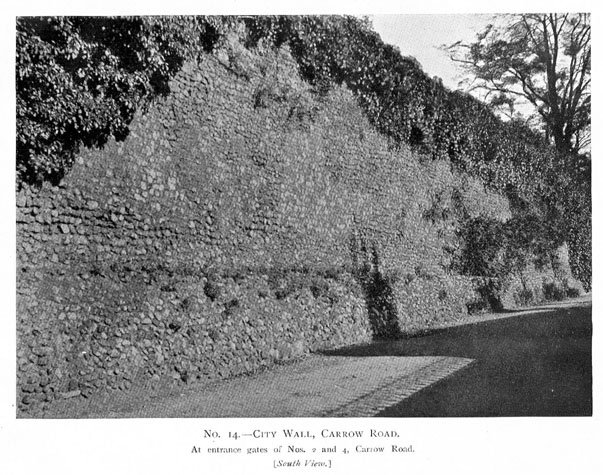

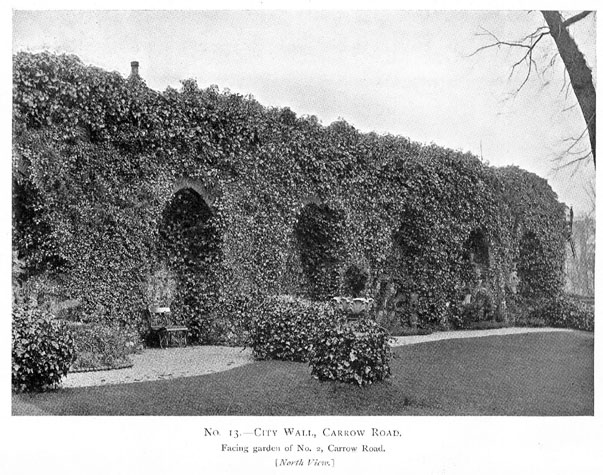

[47] Plan of Carrow Hill published in the report of 1910.

[48] The Black Tower from the west drawn

by L Gurney. [Norwich Castle Museum and Art Gallery 1922.135.FAW 52:F]

[49] Photograph of the Black Tower from the south west, published in the report of 1910.

[50] Photograph of the Black Tower from the south east, published in the report of 1910.

|

Historical Background Report

General description of the historic fabric

The standing defences at Carrow Hill can be divided into three sections that are

obviously closely linked. The first part is the wall and arches in front of the

gardens of Carrow House. The second part is the wall beyond the breach, running

up to the tower and the third part of defences here is the Black Tower itself.

The first part of the standing wall runs west to east from close to the junction

of Bracondale and Carrow Hill and is on the north side of Carrow Hill which is a

19th-century road that follows the line of the outer ditch. The wall is 27.4 metres

long and stands to almost its full height with the wall walk clearly surviving

with the lower courses of a parapet on the outer side.

[2 & 3] The medieval ground level survives inside the wall where there

are six complete arches of the arcade that supported the wall walk.

[4, 5 & 6] These arches are pointed and formed with bricks set with

alternating stretchers and paired headers.

[7 & 8] Each arch has a spalyed embrasure centrally placed to the

arch within the outer face and again constructed in brick.

[9 & 10] At the west end there is a straight joint and the first bricks

of the springing of a seventh arch that was truncated and partly filled in

when the west end was consolidated sometime after the wall was breached here.

[32-04 Up Int Elev] It is clear that the arches continued on to the

intermediate tower at the junction of Bracondale and Carrow Hill that

has been lost. In fact, evidence indicates that there was a continuous

arcade from the angle of the wall at Ber Street just east of Ber Street

Gate, right through to the Black Tower broken only by the lost intermediate

tower...possibly 43 arches in total.

The ground level on the outer face of the wall is lower and the bottom

metre of the wall is battered out.

[32-03 Up Ext Elev] This is not under building but part of the medieval

construction. On the outer side the six loops are formed in brick set

irregularly.

[11 & 12] There are two levels of putlog holes lined in brick

[13] indicating that the main part of the wall was built in three '

lifts' and the parapet would have been raised as a fourth stage of

building and would have been just under 2 metres high with embrasures

and merlons forming battlements. These too would have been formed in

brick but with the main part of the parapet in flint.

At the east end of the wall, immediately before a breach of 20.5

metres, there is part of an eighth arch but completely filled in with

flint work. In the breach, cut through in the 19th century when this

part of the wall was demolished, there were a further 6 arches now lost

but marked out in cobbles in the grass.

The wall running up to the Black Tower is just over 47 metres long

and has part of an arch immediately after the breach and 11 complete

arches.

[14, 15, 16 & 17] The arches and loops here follow the same form

as those in the west section.

[32-06 Mid Int Elev] The loop in the first arch is now blocked and

in the last arch, against the tower, a gateway was cut through the

position of the loop to create a route along a pathway below the tower.

[18 & 19]

The arches are 1.8 metres wide and the piers between the arches are

2.2 metres wide with putlogs placed centrally to the pier and equally

spaced vertically dividing the height into three almost equal sections

or lifts.

[20] The arches are a metre deep in a wall that is 1.8 metre thick

overall. The springing of the arches are approximately 1.5 metres

above the present ground level and the arches are about 2.8 metres

high to the apex in a wall that is just under 4 metres high to the

wall walk.

[32-05 Mid Ext Elev]

Robert Smith has described briefly all the arches and loops listing

where brick work has been replaced or repaired. He has also suggested

that changes along the length imply that the main part of the wall was

built not only in three stages in terms of lifts but may have been

divided along the length with three arches constructed at a time.

The Black Tower has an external diameter of 10 metres and an internal

diameter of 6.5 metres. It stands now 11.2 metres high on the inner

side but where the ground drops away on the side towards the ditch is

13.5 metres high.

[21, 22, 23 & 24] It would originally have been higher with a

crennelated parapet that survived until the 18th century. The tower

is faced in knapped and squared flint and loops and windows are

generally formed in brick.

[32-11 Tow Nor Elev] [32-12 Tow Sou Elev] [32-13 Tow Eas Elev] [32-14

Tow Wes Elev]

The tower had two main chambers. It was entered at ground floor

level by a narrow but curiously tall door way with an arched head formed

in stone in the internal angle between the tower and the wall to the

west.

[25 & 26] The entrance cut through the wall to form a brick

vaulted lobby within the thickness of the wall. Immediately inside

the entrance on the south side is a doorway onto a tight spiral staircase

leading up to the first-floor chamber.

[27, 28, 29, 30 & 31] This staircase turns clockwise with brick

steps and a stone newel. It respects the present ground level of the

tower. It rises partly within the thickness of the tower wall but

also bows outwards and is at the point of the tower where the wall to

the west abuts.

[32 & 33] There is a doorway from the wall walk into the stair

turret just below the level of the chamber floor. That doorway too

has a stone surround with a hood moulding though much damaged.

[34 & 35] There were eight steps at the end of the wall walk up

to the door that were protected by thin parapets on either side.

[36] The staircase continued up beyond the chamber to the level of

the tower roof and the stair turret stood up above the main parapet

as depicted by Kirkpatrick in the early 18th century.

[37]

The lower chamber had eight sharply angled embrasures with narrow

loops, three looking inwards towards the city and five looking outwards

over the ditch or along the outer faces of the flanking walls.

[38 & 39]

The lower storey is tall with what is now an angled offset about 4.7

metres above the floor. Here the wall steps in, the wall of the upper

part of the tower being thinner. This offset could have supported a

timber floor structure but scars in the face of the wall indicate the

webs of a vault with very sharp arches springing from a point 2.7 metres

above the floor.

[32-15 Tow Nor Sec] [32-16 Tow Sou Sec] [32-17 Tow Eas Sec] [32-18 Tow

Wes Sec] Not only does the vaulting appear to be slightly irregular

in its bays but the narrowness of the arches of the vaults suggests

that there may have been a central pier providing support. The entrance

and the projection of the staircase on the west side break the regularity

of the vaulting. The vaulting does not respect the position of putlog

holes which indicates that the drum of the tower was constructed first

and then the form work inserted for the construction of the vaulting.

Much of the upper chamber was altered in the 18th century but the

two main medieval features survive with a narrow arched and chamfered

doorway in brick on the west side leading to the staircase

[40] and immediately to its north a substantial brick fireplace.

This has herringbone brick work across the back but has lost its hearth

and the lintel or arch of the opening and much of inner face of the

flu has collapsed.

[41 & 42]

In the 18th century the chamber was extensively altered by the

insertion of four large round-headed windows.

[43, 44, 45 & 46] These have surrounds formed in brick headers

and photographs and drawings show that the windows had heavy wood frames

with a mullion and Y-shaped tracery. These have all gone though the

rebate for the frames survive. The windows seem to have had semicircular

sills forming a walk-in area within the splay. It is not known if these

openings directly replaced loops or replaced larger but secondary medieval

openings. The early 18th-century drawing of the tower by Kirkpatrick

does show an arch-headed window on the north side which could be medieval.

It should be noted that the Cow Tower, built on a similar scale,

appears to have had simply loops to light the large upper chamber.

There are original loops surviving on the Black Tower but blocked on

the outer side. The sills of these loops are some 1.6 metres above

the offset and too high now to be used. That suggests that the offset

may have been contrived or lowered when the vault was demolished and

the floor constructed some 500mm below its medieval level. That would

certainly fit better with the back crease of the hearth and the threshold

of the doorway onto the staircase.

The upper part of the tower has been lost so it is not clear how the

roof was constructed. The fact that the stair continued to the parapet

level indicates that there was at least a parapet level walk. The

surviving part of the upper wall sets back on the inside just a metre

below the skyline and this ledge would almost-certainly have provided

the support for the roof or platform structure. A newspaper report of a

fire on the roof in 1833 caused by lightning indicates that the roof

covering then was thatch. This may have been a cheap replacement for

lead or tiles but medieval documents record also that several of the gates

were thatched in the 14th century. The report also implies that there

were rooms on three levels in the tower at that stage (see below).

A small blocked opening with an arched head in brick just below the

skyline on the east side of the tower indicates that there was some sort

of feature here at parapet level though its function is unclear. Was a

wider opening required to look down from this level towards the river?

Documentary evidence:

In the early 13th century, the land inside the wall was held by a

priest called Nicholas de Berstrete. About 1216 he granted the land

to one Sibrand Prat for 30 shillings. This included part of the land

'which was John le Botelers, from the Gates of Berestrete, lying

between the land of Carrowe and the King's way, which extendeth from

the Gates of Berestrete to Conesford in breadth, and in length from the

Ditch of the City to the Pathway which extends from the King's way

aforesaid to the Church yard of St Peter of Southgate.'

[Fitch, page 1]

This was a very large piece of land covering all the steep hillside

from Ber Street Gate to King Street and everything south of that. The

document shows clearly that the city certainly extended as far south as

Conisford Gate by the early 13th century and there was already a ditch

marking the city limit which presumably followed the present course of

the wall down Carrow Hill. It is also interesting that although Boteler

owned the property in the 12th century his name survived for Carrow Hill

was referred to as Butlers Hill until at least the late 19th century and

the Black Tower was variously referred to as Botelier's Tower or

Butler's Tower. Ann, the daughter of Sibrand granted this property,

to the Church of St Mary along

with all her tenements in the city and a mill 'before the Gates of

Berstret.'

The Black Tower was also known as the Governor's Tower, apparently

because it housed a military commander during a siege.

[Blyth, page 5] In 1451 and 1481 the Agistment for the Walls

records that North Conesford Ward were responsible for repairs to the

tower.

[Liber Albus, f. 177; Hudson & Tingey, vol. II, pages 313-15]

'On the top of Butterhills stands a fair large and lofty round

tower, all faced with black flint, having a decayed watch tower or

turret on the top of the staircase, which is on the N. W. side of the

tower. At the Assembly on St. Matthews day, 33 Eliz. 1591, Mr. Thos.

Pecke, Alderman, promised to give �4 towards the covering of this tower,

which is called

Black Tower.' [Fitch, page 3]

In 1625 the tower was made into a prison for 'unruly, infected

persons.' In 1621 two pest houses were re-erected on the site. In

1630 six houses were erected near to it, as pest houses and in 1636

the Black Tower was again 'made up' owing to plague.

[Blomefield, pages 376, 377 and 379]

In 1748 Samuel Bruister acquired the land inside the walls on a

hundred year lease and appears to have opened a pleasure garden here.

[Trevor Fawcett, article on Norwich Pleasure Gardens in Norfolk

Archaeology] In 1768 public breakfasts were held in the gardens and

in the evenings the walls were illuminated and there were illuminated

walks. By 1771 the walls and the gardens were privately owned and the

Black Tower was called Mackarel's Tower.

Some time before 1789 the tower was converted into a snuff mill ...

Hochstetter's map of Norwich of 1789 identifies it as such.

[NAU Report 161, page 2]

A tablet dated 1817 attached to the Black Tower records the conversion

of part of its surroundings to public gardens.

[SMR NF26487]

In July 1833,

During a severe thunderstorm, a fire-ball, apparently the size

of a man's head, fell upon the thatched roof of the Black Tower,

Butter Hills, Norwich. The middle and lower rooms, occupied by a person

named Brooks, and the upper story, where a society of artisans were

assembled for astronomical observations, were entirely consumed. The

society's valuable apparatus were destroyed.

[Annals, vol. I, page 324]

Map evidence:

Early maps show that the wall and all the intermediate towers

between Ber Street and King Street survived until the late 18th

century. There were no buildings on the line of the ditch and no

buildings inside the walls. On King's map of 1766, the Black

Tower is identified as the Earl of Buckinghamshire's Tower.

Carrow Hill House, or at least the first house on the site, was

built between 1766 and 1789 for it is shown as a long narrow block

immediately behind the wall on Hochstetter's map of 1789. On that

map the Black Tower is identified as a Snuff Mill. The outer ditch

running down Carrow Hill was dry and was open land with a pathway winding

down from Bracondale to King Street at a point just outside the gate.

There were gardens laid out against the wall on the lowest section of

the wall below the lower tower.

Millard and Manning's map of 1830 shows a road running down Carrow

Hill, down the line of the ditch. This is said to have been constructed

in 1817 and continued across the line of King Street to a new bridge

south of the Boom Towers.

By 1873, the year Morant's map was published, the road down

Carrow Hill was called Butlers Hill. Both the large house south of

Southgate Lane and Carrow Hill House in its present form had been built

for they are shown on that map. The wide breach in the wall immediately

in front of Carrow Hill House had been created by demolishing a section

of the wall. The house was built close to the wall because the plot is

tightly confined by the steep drop immediately beyond the house. In fact

the house is partly terraced out over the slope at the back.

By 1885, the year of the first edition of the Ordnance Survey map,

the wall and tower on Bracondale north of the surviving section had also

gone and the wall and the landscape were much as now. The hillside below

Carrow Hill House, running down to St Peter's Church and King Street,

was then called the Wilderness. The steep slope was laid out with

terraced paths and narrow flights of steps.

By 1910, when a map of this section was published in the report on

the walls by A Collins, Butlers Hill was called Carrow Road.

[1910 report map 1 opposite page 12] Its name was changed to Carrow

Hill later in the 20th century. By 1910 there were steps set out

inside the wall running down the hill beyond the Black Tower.

[47]

Historic views and historic photographs:

John Kirkpatrick's drawing of the 'Great Tower upon Butter

Hills', [Norwich Castle Museum 1894.76.1695] although otherwise

unnamed is of the Black Tower, rather than of the lower tower. It

shows the tower, with the taller stair turret adjoining to the right

and with parts of the wall visible to left and right. The first arch

in the wall to the west of the tower is included and the line of the

wall walk is shown clearly with the crenellations of the outer parapet.

The wall down to the lower tower has battlements but no indication of

a wall walk. The drawing dates from the first quarter of the 18th

century and shows one large arched window to the chamber on this inner

side.

The sketch by L Gurney [NWHCM 1922.135.FAW 52:F] entitled Bracondale

Tower presumably dates from the 19th century and is a much more

romanticised view with the tower framing the view from the west down a

heavily wooded valley to the river beyond.

[48] The arch through the wall and steps down to the ditch are shown

to the left of the tower and the upper window on this side is shown

with Y-shaped tracery presumably in wood set within the brick arched

opening. The drawing indicates that part of the battlement on the top

of the tower survived.

The same wooden window frame and tracery is shown in the window on

the south-east side in the photograph published in the 1910 report.

[Collins, 1910, plate 10] The photographs of the wall to the west

of the tower

[plates 11-14] show those sections much as now though heavily covered

with ivy.

[49 & 50]

Archaeological reports:

In 1971 some sherds of seventeenth-century pottery were dug up from

just under the surface inside the city wall near the tower.

[SMR NF51]

CONDITION SURVEY

List of known repairs:

The report on the walls in 1970 states that there were serious

cracks at the base of the Black Tower and recommended remedial work.

Extensive repairs to the tower were undertaken in the early 1990s.

When the tower was scaffolded, the structure was examined by the Norfolk

Archaeological Unit and analytical reports were produced by Robert Smith.

These reports include detailed assessments of the flint work and surviving

brick work. They were written over several years and are reproduced in

the appendix:

- The wall running up to the Black Tower was surveyed in 1991

- The first draft of the report on the section of wall to the west is

dated October 1991

- A 'final' report is dated March 1993

- The Black Tower was surveyed in May 1995

- Report No 161 on the Black Tower by the Norfolk Archaeological

Unit is dated December 1995.

Summary of present condition:

The walls and tower are in a very good state of repair and in the

medium term should need little work apart from regular maintenance to

avoid major problems

Principal conservation problems:

However, there are several problems that should be tackled now

before they develop and require more major work.

- The loop on the south side has flints broken away on either

side making the opening wide enough to climb through even though

it is set relatively high above the path. One boy caught in the

tower while we were surveying told me that was how some climbed

into the tower. He had actually been given help to scramble on to

the wall walk and had entered the tower by climbing down the staircase.

- The doorway from the wall walk should be sealed with a light but

strong grill set as far back into the opening as possible.

- High on the west side of the tower, a self seeded buddleia has

become established and has thrown forward a large area of flint.

This is above the pathway leading under the tower from the gateway

in the last arch. This must be repaired as it is dangerous.

- Shedding flints on the face and top of the wall

A general problem that should be monitored annually.

- Intrusion of woody stemmed plants

A general problem but here much more difficult to tackle because

the tower is so high.

- Deterioration of the brickwork

Not a major problem as the brick work of the wall arches and the

brick work on the tower has been repaired several times since the

19th century. Robert Smith's report describes each loop and

arch briefly but identifies repairs or bricks replaced at several

different periods.

|