|

[3] The west or outer side of the wall.

[4] The west or outer side of the wall.

[5] The east or inner face of the wall.

[6] The east or inner face of the wall.

[7] The east or inner face of the wall.

[8] Putlog on the outer or west face of the wall.

[9]The wall from the north west with the truncated base of a lost tower in

the foreground.

[10] Map of Barn Road in 1910 from the report published by A Collins.

[11] View of Heigham Gate in the early 18th century attributed to James

Reeve [Norwich Castle Museum and Art Gallery 1894.76.FAW 306: F]

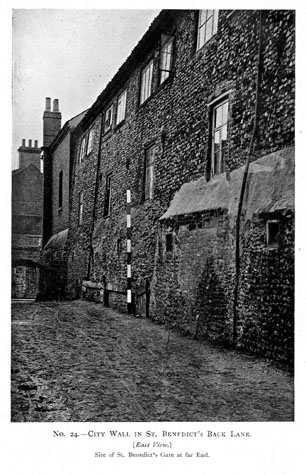

[12] View along St Benedict's Back Lane looking south towards the site

of St Benedict's Gate. The houses were built up to and over the

wall on the outer side on the line of the ditch.

[13] The east or inner face of the wall.

[14] The east or inner face of the wall.

[15] The east or inner face of the wall.

[16] South side of arch from the outside, from the north east.

[17] South side of arch from the outside, from the north east.

|

Historical Background Report

General description of the historic fabric

This section of the surviving wall is at the north-west side of the city,

south of the site of Heigham Gate and immediately north of the site of St Benedict's

Gate. The standing section is 57 metres long with the remains of six arches of the

wall-walk arcade and, after a breach where three arches have been lost, there is a seventh arch standing in isolation at the north end. The surviving section was 19 metres north of the gate at St Benedict's and there would have been a further three arches between the gate and this part.

[3, 4 & 5]

This section of the wall was constructed in the late 13th or early 14th

century on the top of the bank of an earlier defence. The wall was built

on the front edge of the bank and stands on shallow foundations of layers

of flint and mortar in a shallow trench cut into the top of the bank.

The wall appears to have had an inner arcade from the start, the arches

supporting a wall walk with an outer crenellated parapet. Although the

surviving arches are badly decayed sufficient remains to show that the

wall was constructed in much the same way as the more substantial sections

surviving at Carrow Hill. The decay of the flintwork is so great that it

is difficult to take precise measurements but the arches appear to be about

2.6 metres wide, slightly wider than at Carrow Hill. They were regularly

spaced about 2.1 metres apart, again slightly wider than at Carrow Hill.

This may explain why there appear to be fewer battlements in this section,

given the distance, than in other parts of the walls. The arches were about

1.8 metres high from the ground to the springing and 2.4 metres high overall

to the apex. The arches were formed with two rows of headers.

[6] In the centre of the piers are the remains of putlog holes lined with

bricks at two heights implying that the main part of the wall was constructed

in three stages or lifts.

[7 & 8] The putlog holes run at the same level all along the main part

of the surviving section. There is a slight change of level in the detached

arch at the north end which probably reflects the fact the wall stepped down

at several points as the wall dropped down the slope towards Heigham Gate

and the river.

On the outer side of the wall was a very broad and deep ditch whose

dimensions must reflect the amount of water that drained down the ditch

down Grapes Hill to the south.

[16-01 Map] Excavations here by E M Jope in 1948 established that the ditch

here was over 18 metres wide and about 5.2 metres deep with a flat bottom.

The water table was 4.5 metres below the surface so the ditch must always

have been filled with standing water however much or however little drained

down the hill. More significant perhaps is that the level of the river is

only about 4 metres below the present ground level.

Archaeological finds suggested that the ditch had been kept relatively

clear until 1500. It had then slowly silted up and systematic filling-in

began about 1700.

Archaeological excavations of the wall in 1951 and 1953 were published

in 1957 by Hurst and Golson. The drawings of the site show that at that

stage the bases of six complete arches were uncovered north of the tower

and after a gap (where there had been two more arches) the north jamb of

the ninth arch was excavated. South of the tower the dig uncovered the

bases of six arches where there are now only four and the north side of

the fifth.

Jope also excavated the surviving base of a tower on the outer side of the wall.

[16-02 Plan] This was semicircular to the ditch and was described as

three-quarter circular inside.

[9] Kirkpatrick in the 18th century seems to have adopted the term horse

shoe-shaped for this form of tower. The tower was 7 metres across with

external walls just under 2 metres thick. The internal wall was much thinner,

only 540mm, and Jope considered this to be integral and original to the tower.

The excavation plans show arches on either side of the tower and overlapping

or cutting across the line of the outer wall of the tower. This is a very

strange arrangement which would seem to weaken the tower and is certainly

not found anywhere else on the defences in Norwich. Jope's plans must be

correct as part of the south arch survives. The arrangement might imply

that the tower was added but the irregular spacing of the arches here suggests

that the tower was an integral part of the primary construction. The threshold

of a doorway into the tower was uncovered with steps in red medieval bricks

and part of a jamb in oolitic limestone.

[Jope 1948, plates 111a and b]

The front face of the tower had a chamfered off set and the footings

continued down some 3 metres below the present ground level. This must

reflect the fact that masons were building the flint walls out into an

existing and water filled ditch. There were 3 putlog holes lined with

bricks immediately above the chamfered offset. The tower had a medieval

mortar floor 1.5 metres below existing ground level. On the inner side

of the wall was a roadway - the lane inside the wall - that had a pebbly

surface.

[Jope, 1952 page 296]

In 1953 when an inspector from the Ministry of Works wrote a report

on the walls, there were still some face flints on the tower and the

interior of the tower was lime washed.

The surviving arches follow the descent of the slope down to the river

although the modern road has levelled out the gradient.

[16-03 Ext Elev, 16-04 Int Elev, 16-05 Reconstruc] Presumably the wall

walk and the parapet also stepped down along the length of the wall between

St Benedict's and Heigham Gate.

Documentary evidence:

According to Blomefield's transcription of the last leaf of the Book of

Customs, from Heigham Gate to St. Benedict's Gate (incorporating both

sections of Barn Road) there were 79 battlements along the walls.

[Blomefield, page 98] As the distance between

the gates was about 235 metres, and as elsewhere the merlons were about

2 metres wide, there would seem to be too few battlements. Either the

assessment is wrong or part of the wall may not have had a crenellated

parapet.

Blyth notes that this stretch of wall 'from St. Benedict's to Heigham

gate is built upon within and without.' [Blyth, page 4] [10]

Map evidence:

Of all the early maps, Kirkpatrick's map [Norwich Castle Museum 1894.76.1682: F]

is the only one that depicts this section of the wall accurately, showing

two towers between Heigham Gate and St Benedict's. However, the 18th-century

maps by Hoyle, Blomefield and King do show that there were few buildings

in this part of the city, presumably because it was low lying and damp.

There were no buildings outside the walls between the gates and inside the

walls there was a large area of open land between Nether Westwick and Upper

Westwick, later called St Benedict's Street.

Archaeological evidence suggests that the ditch along this section of

the defences was filled in about 1750 and after that change and development

was rapid. By 1789, when Hochstetter surveyed the city for his map, much of

the land was still open but he shows houses encroaching on the ditch.

Buildings in the centre between the gates, just north of this section,

appear to straddle the wall and imply that by then at least part of the

wall had been removed. In the 19th century large numbers of small,

tightly-packed houses were built, in part associated with industrial

development. Inside the walls, just south of Heigham Gate a Crape factory

was built and there were gas works and iron works built outside the ditch

to the north west.

By 1885, the date of the first edition of the Ordnance Survey map,

[sheet LXIII.11.17] there were houses built over the ditch, hard against

this surviving section of wall, with gardens and frontages to Barn Road.

The lane inside the wall, then called St Benedict's Lane, was free of

encroachment, though beyond this section to the north the wall had been

demolished and the lane was blocked with buildings. The same buildings

are shown on a sketch map published with the report of 1910 and these

presumably survived until 1942 when much of the area was damaged by extensive

bombing. [10]

Historic views and historic photographs:

A view of Heigham Gate by James Reeves shows an arch to the south of

the gate which, with the surviving arches in this section close to St

Benedict's Gate, would suggest that the whole wall between the gates

had an arcade on the inner side to support the wall walk. [Norwich Castle

Museum 1894.76 FAW 306 :INT][11]

A photograph of the houses built against the walls taken before 1910

was published in Collins Report. [Collins 1910 plate 24] [12] This is

looking down the inner side of the wall from the north towards St

Benedict's Gate. The remains of the gate can be seen clearly at the

far end of the alley. The houses built on the outer side of the wall,

over the site of the ditch, were of three storeys. The ground floor wall

has shadows and patching indicating the position of arches. Above a

rough irregular offset, in part rendered, the upper floors of the houses

also appear to be built in flint. Was this material robbed out of the

walls when the houses were built? A surveyors staff in the photograph

shows that the medieval part of the wall was then about 9 feet high from

the level of the lane.

Archaeological reports:

- An excavation in 1948 of a bomb damaged area of Barn Road (TG22450888)

revealed, in a section cut through the city defences, a semicircular

bastion, which was seen and noted by Kirkpatrick in the eighteenth

century.[SMR NF19]

- Excavations east of the city wall in 1954-55 revealed flimsy clay

lump huts associated with 13th-century pottery sealed by the city bank

and there were several huts built behind the city bank c.1300 onwards.

[SMR NF 21]

- 3. The same report records the discovery of an earlier bank, dated

to the middle of the 12th century, with a ditch that was 12ft deep and

60ft wide. Excavations of the foundations of some 18th-century houses

found that these were built over the city ditch.

- 4. In 1970 a bastion (TG22500905) was seen in a sewer trench near

the Westwick Street junction. [SMR NF26013] Measurements of

this were apparently taken by E B Green, but these have not been

located. This was presumably the tower closer to Heigham Gate.

CONDITION SURVEY

List of known repairs:

Not available at this stage.

Summary of present condition:

The general condition of the wall is poor mainly because so few face

flint survive and the exposed core has such an irregular surface that

water is held back and penetrates into the wall around the flints rather

than running off. [13]

The problems were clearly identified in a report by the Ministry of

Works in 1953. That report is worth quoting in full here as the situation

has not been remedied in the intervening 50 years.

"Barn Road with Base of one Tower

As a result of enemy action and some subsequent archaeological excavation

portions of the wall are now exposed on both sides, and quite a lot is

known about their construction and date. The present surface of the ground

at this point is much above the 14th Century level, and it is known that

the wall face exists at a lower level, whereas the standing remains are

mostly of corework. If this accumulation of earth were removed, it would

be found that these remains are really higher and more impressive than

they now seem to be, with good facework at the base. They would also be

found to be linked together, whereas now they are in two parts. It is

most desirable that this earth be removed and a scheme be prepared for a

small open space enclosing the remains of the wall and the base of the

tower, which has excellent masonry. With this done, as well as the City

Wall on the other side of St Benedict's Gate adequately preserved, in the

manner advocated in the foregoing section, there would be a second most

impressive entry into the medieval city, complementary to that astride

King Street.

Before the removal of any earth from the base of the wall, the existing

arches and other remains must be carefully consolidated and those arches

which have fractured should have small reinforced concrete beams inserted

in the corework above the arch stones, or the level where they have been.

All concrete work must, of course, be covered by core or facework as the

case may be. Again, the ends of each section must be left rough but sound.

The very high quality facing flints in the base of the Tower are now

falling away rapidly and already the deterioration since exposure has been

considerable. All loose flints must be re-set in complete character with

the undisturbed facing and the wall-tops waterproofed by the addition of

a small amount of cement to the lime mortar. In the debris now in or

just outside the tower should be found an original door jamb stone and

step which was in situ at the time of excavation. If found, this should

be re-set in its original position.

After excavation of the earth, the newly exposed wall facing should be

treated as necessary.

Urgent: �120

Necessary �350."

Principal conservation problems:

- Fractures implying possible collapse:

There are fractures in the flint work in the apex of the arch

immediately north of the site of the tower. This should certainly be

monitored. If water is penetrating into the core it is probable that

the arch will collapse like the south arch.

[14 & 15]

- Shedding flints on the face and top of the wall

There are several places at the base of the wall where areas of

flint are loose or have dropped out. These areas should be cleaned

back and the flints re-bedded in a soft lime mortar. Areas of core

work around the south arch are also in a bad condition and flints

should be firmly fixed into new mortar. It does not seem necessary

at this stage to re-point any sections of the wall. Generally the

flints on the top of the wall are securely bedded and the only real

problem is to ensure that water drains off the wall top quickly.

- Intrusion of woody stemmed plants

Not a particularly serious problem here at the moment but buddleia

and other weeds within the sunken base of the tower should be removed

annually.

- Deterioration of the brickwork

As elsewhere around the walls, the brick work only becomes a

problem when the flint work above the arches deteriorates to such

an extent that water penetrates into the brick work from above.

Then problems with the arch develop rapidly. Here all the arches have

lost most of their bricks as the mortar has weakened.

[16] In the south arches, so much of the brickwork and arch has

dropped out that there is virtually no way to fix back the few bricks

still in place.

[17] It would seem impractical to use pins or steel holdbacks for

these badly worn bricks and if a stronger mortar was used this would

cause more problems with larger areas of flint and brick being pulled away.

|